There was a Pig that sat alone

Beside a ruined Pump:

By day and night he made his moan—

It would have stirred a heart of stone

To see him wring his hoofs and groan,

Because he could not jump.

Right now I am feeling the deepest empathy with Lewis Carroll’s Pig—whose Tale you’ll encounter in the author’s Sylvie and Bruno, circled by some charming rhymes about little birds … Oh what the hell. You need a taste of the birds’ story too: “Little Birds are bathing/ Crocodiles in cream,/ Like a happy dream:/ Like, but not so lasting–/Crocodiles when fasting,/ Are not all they seem.”

Aging is a fascinating and complex process. You think you know beforehand what it’s like, but it’s hard to fully comprehend even when you’re going through it. Yes, there are compensations. You’ve probably heard therapists, essayists and annoyingly positive people caroling our increased wisdom and empathy. And that is often there—vide: my understanding of porcine grief. But there are losses, and here’s one of mine.

I will never be able to jump again.

For a while I thought I could get my jump back if I faithfully did exercises to strengthen my glutes and quads, thus—I hoped—bypassing those annoyingly frayed menisci. Almost got there—teeny little moments of feet leaving the floor while I leaned over the kitchen counter putting much of my weight on my arms. But then I fractured a hip and needed a replacement and when I asked my usually very encouraging physical therapist if she could help me with my jump, she said firmly, “No. You can’t jump any more.”

I guess that makes sense if you have a titanium ball cradled in a ceramic cup where your femur used to be. You really don’t want to jolt anything.

Jumps mean a lot more when you realize you can’t do one. Unless propelled by sheer terror, people usually jump for pleasure—unexpected joy, sport, kids’ games and dancing. One of the things I love most about the video of Redemptorist nuns and priests dancing to Jerusalema (a song created by South African DJ and record producer Master KG and featuring South African vocalist Nomcebo) is that a few of the aged nuns can barely shuffle their feet, let alone jump, but the music still animates those failing bodies and shines through the dancers’ eyes.

There’s meaning to the way people jump. In the 1950s, famed photographer Philippe Halsman began photographing people jumping, many of them famous, and collecting the work in a book. There’s Marilyn Monroe, legs bent back at the knee and tucked behind her like a little girl jumping rope; Audrey Hepburn flying through the air, arms and legs extended; Richard Nixon, feet tight together and seeming only inches from the floor; Eartha Kitt elegant even in flight—the lines of her lovely dress echoing the lines of her lithe body. Salvador Dali’s entire studio, including easel, water from a jug, and a couple of cats, jumps with him. Halsman called his discoveries jumpology and insisted that a single jump revealed a subject’s deepest impulses, his or her very soul.

This was actually brought home to me when I was in my early twenties and taking classes with acting coach Anthony Abeson who, at one point, instructed me to jump. Ridiculously self-conscious, I stood and stared at him, hands dangling, feet glued to the floor. “Jump,” he insisted. And finally I did.

The result was interesting. There was an intense heaviness at take-off, Abeson commented, but “at the apex, when you were in the air, I saw a moment of radiant, all-consuming joy. You were flying. It vanished in seconds and you thunked down.”

I think most of us have experienced something like this—those blessed times when words, actions, and ideas flow. If you’re an athlete, you’re in the zone and can’t lose the game. If you’re acting everything that happens onstage, even if you fall or forget a line or choke a little on a glass of water, all of it fits, perhaps even becomes an addition to an inspired interpretation.

I treasured Tony Abeson’s comment because if I was capable of the flying moment he glimpsed, I would surely be able to find it again.

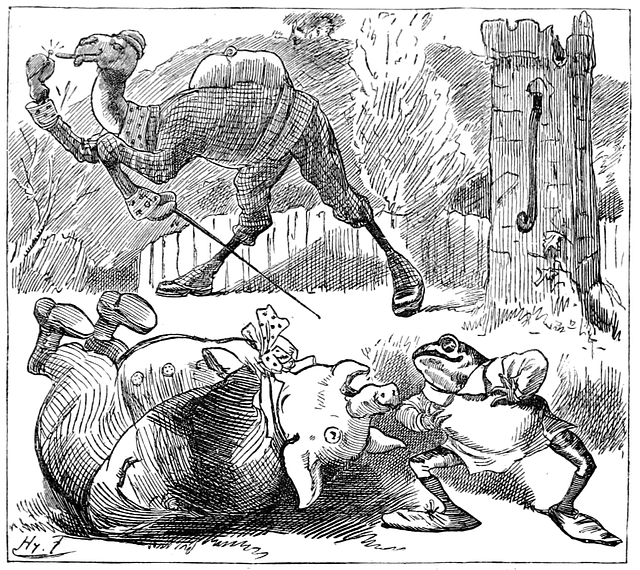

I regret to tell you that Lewis Carroll’s Pig, despite coaching from a passing Camel and a Frog, never does learn to jump and sinks into despair.

I, however, am learning to celebrate the things this imperfect body can still do: walk through the garden without a cane, stand by the stove and cook garlicky vegetables, play silly games with my granddaughter. And dance through a Zumba class, even if I have to do it seated and all I can manage as the teacher leaps is a shuffle.

Here are the Little Birds again to see you out:

Little Birds are tasting

Gratitude and gold,

Pale with sudden cold:

Pale, I say, and wrinkled—

When the bells have tinkled,

And the Tale is Told

For more on Halsman’s work: https://www.magnumphotos.com/arts-culture/philippe-halsman-jump-book/

love the video and your thoughts. Isn’t it true that we never really thought of aging until one day we realized that there were things we no longer could do.

Leaps of imagination count.

I haven’t given a lot of thought to jumping UP lately – I would not do any better than Nixon, I’m sure – but I do remember concluding, at least 10 years ago, that jumping OFF anything higher than a rather low chair was not a good idea. This made me interrogate my memory to see if I could discover the age at which my inner monologue dropped the phrase, “I should learn how to do a cartwheel” and adopted in its place, with more conviction, the phrase, “I will never do a cartwheel.” I only know it was a long time ago. Thank you for reminding me about “Sylvie and Bruno” which I heard about first only recently.